A preserved Stone Age deer tooth pendant has revealed the identity of the woman who wore it after scientists extracted her DNA from the surface.

The tooth – with a hole drilled for a leather lace – was unearthed from a Siberian cave and subjected to a new method of retrieving ancient DNA specimens.

The process – carried out by scientists from the Max Planck Institute (MPI) for Evolutionary Anthropology – revealed that the pendant had been made up to 25,000 years ago.

By isolating the wearer’s DNA from the artefact, scientists discovered she was closely related to hunter-gatherers from the nearby Altai Mountains in Russia.

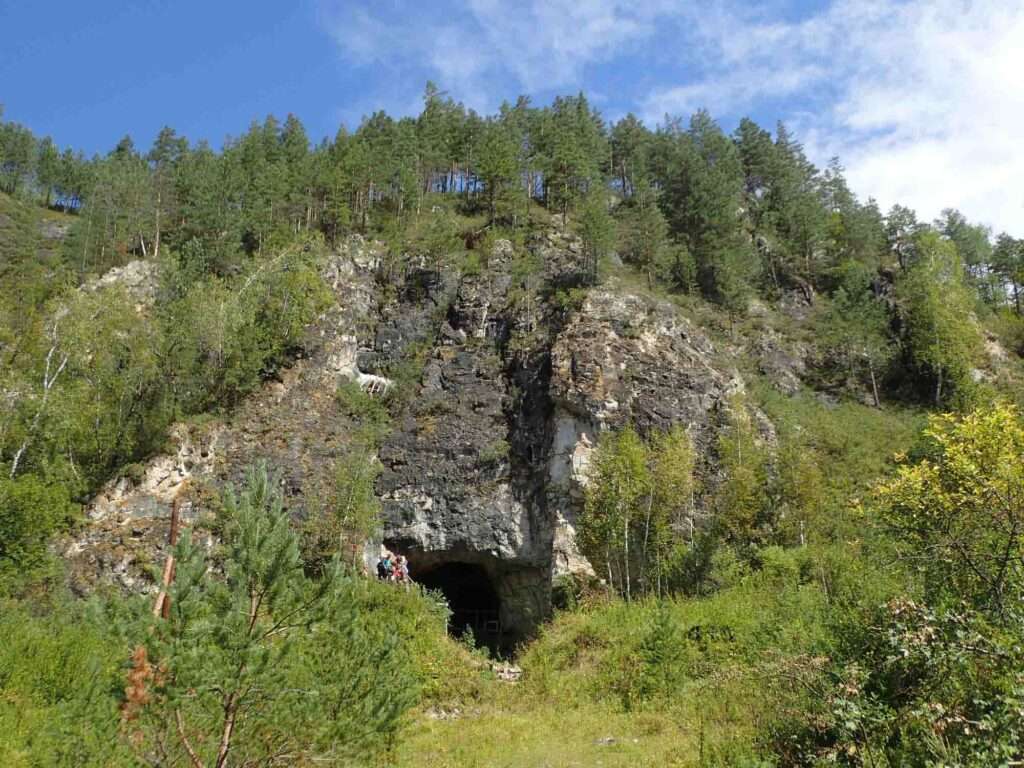

The pendant – found in the Denisova Cave – is the first ancient artefact to give up its human secrets.

Scientists described the process as a “washing machine” for revealing the true history of objects owned and handled by our human ancestors.

But it only works if the objects have been extracted to eliminate contamination with modern DNA using gloves and evidence bags like crime scene investigators.

MPI expert and study lead author Elena Essel said: “One could say we have created a washing machine for ancient artefacts within our clean laboratory.

“By washing the artefacts at temperatures of up to 90 degrees centigrade, we are able to extract DNA from the wash waters, while keeping the artefacts intact.

“The amount of human DNA we recovered from the pendant was extraordinary – almost as if we had sampled a human tooth.”

The MPI hailed the process as a breakthrough.

In a statement from 3rd May obtained by Newsflash, they explained: “To preserve the integrity of the artefact, they developed a new, non-destructive method for isolating DNA from ancient bones and teeth.

“From the DNA retrieved they were able to reconstruct a precise genetic profile of the woman who used or wore the pendant, as well as of the deer from which the tooth was taken.

“Genetic dates obtained for the DNA from both the woman and the deer show that the pendant was made between 19,000 and 25,000 years.

“The tooth remains fully intact after analysis, providing testimony to a new era in ancient DNA research, in which it may become possible to directly identify the users of ornaments and tools produced in the deep past.”

They added: “Artefacts made of stone, bones or teeth provide important insights into the subsistence strategies of early humans, their behaviour and culture.”

They went on: “However, until now it has been difficult to attribute these artefacts to specific individuals since burials and grave goods were very rare in the Palaeolithic.

“This has limited the possibilities of drawing conclusions about, for example, the division of labour or the social roles of individuals during this period.”

Although tools and jewellery made from bones are rare, they are likely to retain more of the user’s genetic material, said the team.

They explained: “Because these are more porous and are therefore more likely to retain DNA present in skin cells, sweat and other body fluids.”

Prof Marie Soressi from the Faculty of Archaeology at Leiden University, Netherlands, supervised the study.

She said: “The surface structure of Paleolithic bone and tooth artefacts provides important information about their production and use.

“Therefore, preserving the integrity of the artefacts, including microstructures on their surface, was a top priority.”

Researchers tested the influence of different chemicals on the surface of archaeological bone and tooth pieces and eventually created a non-destructive phosphate-based method to extract DNA.

According to the MPI, experts first applied the method to a set of artefacts excavated at a cave in Quincay, western France, between the 1970s and the 1990s.

The institute announced: “Although in some cases it was possible to identify DNA from the animals from which the artefacts were made, the vast majority of the DNA obtained came from the people who had handled the artefacts during or after excavation. This made it difficult to identify ancient human DNA.”

It added: “To overcome the problem of modern human contamination, the researchers then focused on material that had been freshly excavated using gloves and face masks and put into clean plastic bags with the sediment still attached.

“Three tooth pendants from Bacho Kiro Cave in Bulgaria, home to the oldest securely dated modern humans in Europe, showed significantly lower levels of modern DNA contamination; however, no ancient human DNA could be identified in these samples.

“The breakthrough was finally enabled by Maxim Kozlikin and Michael Shunkov, archaeologists excavating the famous Denisova Cave in Russia. In 2019, unaware of the new method being developed in Leipzig, they cleanly excavated and set aside an Upper Paleolithic deer tooth pendant.

“From this, the geneticists in Leipzig isolated not only the DNA from the animal itself, a wapiti deer but also large quantities of ancient human DNA.

“Based on the analysis of mitochondrial DNA, the small part of the genome that is exclusively inherited from the mother to their children, the researchers concluded that most of the DNA likely originated from a single human individual. Using the wapiti and human mitochondrial genomes they were able to estimate the age of the pendant at 19,000 to 25,000 years.

“In addition to mitochondrial DNA, the researchers also recovered a substantial fraction of the nuclear genome of its human owner. Based on the number of X chromosomes they determined that the pendant was made, used or worn by a woman.

“They also found that this woman was genetically closely related to contemporaneous ancient individuals from further east in Siberia, the so-called Ancient North Eurasians for whom skeletal remains have previously been analysed.”

Prof Matthias Meyer – who heads the MPI’s Advanced DNA Sequencing Techniques Group – said: “Forensic scientists will not be surprised that human DNA can be isolated from an object that has been handled a lot. But it is amazing that this is still possible after 20,000 years.”

Now the scientists plan to apply their method to many other objects made from bone and teeth in the Stone Age to learn more about the genetic ancestry and sex of the individuals who made, used, or wore them.

To find out more about the author, editor or agency that supplied this story – please click below.

Story By: Thomas Hochwarter, Sub-Editor: Marija Stojkoska, Agency: Newsflash

The Ananova page is created by and dedicated to professional, independent freelance journalists. It is a place for us to showcase our work. When our news is sold to our media partners, we will include the link here.