Modern human brains make fewer mistakes than those of Neanderthals despite being of similar size, scientists in Germany have found.

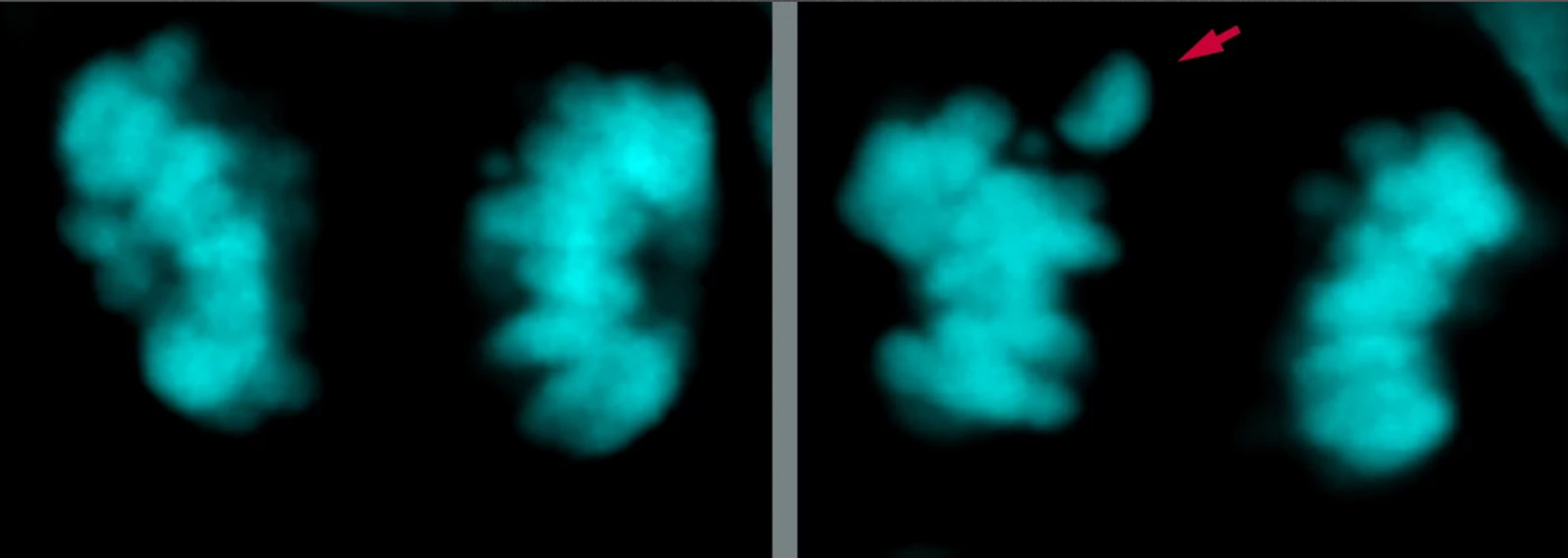

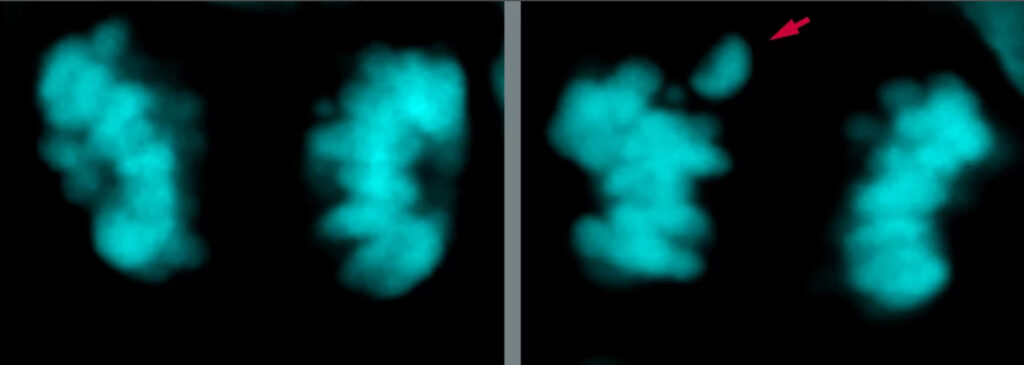

Researchers from the German Max Planck Institute have discovered that neural stem cells – the cells from which neurons in the developing neocortex derive – spend more time preparing their chromosomes for division in modern humans than in Neanderthals.

This results in fewer errors when chromosomes are distributed to the daughter cells in modern humans than in Neanderthals or chimpanzees.

It means modern humans are less prone to conditions like cancer or trisomes, where three copies of a chromosome appear in cells instead of two.

It could also have consequences for how the brain develops and functions, according to the Max Planck Institute research groups.

The neocortex is the largest part of the outer layer of the brain.

It is unique to mammals and involved in higher-order brain functions such as sensory perception, cognition and language.

Neanderthals are the closest evolutionary relatives of humans living today.

Sea Soaked Up 50,000 Tonnes Of Russian Gas From Nord Stream Sabotage Blast, Says Study

An astonishing 50,000 tonnes of methane unleashed by explosions on the Nord Stream pipelines that pumped Russian gas to the West was trapped in the Baltic Sea, say experts. Scientists studying the 2022 suspected sabotage say most of the natural…

The oldest known Neanderthals are about 400,000 years old. They became extinct around 40,000 years ago.

The Max Planck Institute research groups focused on substantial changes in amino acids.

This development occurred when the ancestors of modern humans split from those of Neanderthals and their Asian relatives, the Denisovans.

Amino acids are organic compounds which could be described as building blocks of proteins in cells and tissues.

The research group at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics in Dresden introduced the modern human variants in mice.

Felipe Mora-Bermudez – the lead author of the study – explains: “Mice are identical to Neanderthals at six amino acid positions, so these changes made them a model for the developing modern human brain.

“We found that three modern human amino acids in two of the proteins cause a longer metaphase, a phase where chromosomes are prepared for cell division.

“This results in fewer errors when the chromosomes are distributed to the daughter cells of the neural stem cells, just like in modern humans.”

The scientists then introduced the ancestral amino acids in miniature organ-like structures grown from human stem cells in the lab to determine whether the Neanderthal set of amino acids has the opposite effect.

Mr Mora-Bermudez said: “In this case, metaphase became shorter and we found more chromosome distribution errors.”

According to Mora-Bermúdez, this shows that modern human amino acid changes in certain proteins are responsible for the fewer chromosome distribution errors seen in modern humans as compared to Neanderthal models and chimpanzees.

The scientist added: “Having mistakes in the number of chromosomes is usually not a good idea for cells, as can be seen in disorders like trisomies and cancer.”

Wieland Huttner is a research group leader at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics.

Huttner said: “Our study implies that some aspects of modern human brain evolution and function may be independent of brain size since Neanderthals and modern humans have similar-sized brains.

“The findings also suggest that brain function in Neanderthals may have been more affected by chromosome errors than that of modern humans.”

Svante Paabo – the director of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig – added: “Future studies are needed to investigate whether the decreased error rate affects modern human traits related to brain function.”

The study was published under the title ‘Longer metaphase and fewer chromosome segregation errors in modern human than Neanderthal brain development’ in the peer-reviewed, academic journal Science Advances, on Friday, 29th July.

It was authored by Felipe Mora-Bermudez, Philipp Kanis, Dominik Macak, Jula Peters, Ronald Naumann, Lei Xing, Mihail Sarov, Sylke Winkler, Christina Eugster Oegema, Christiane Haffner, Pauline Wimberger, Stephan Riesenberg, Tomislav Maricic, Wieland B. Huttner and Svante Paabo.

Neanderthals lived in Europe and in the Middle East as well as in western Siberia and Central Asia.

Their name comes from the site where workers in a limestone quarry discovered parts of a skull and bones in 1856 – the Neandertal near Duesseldorf, the capital of the German State of North-Rhine Westphalia. “Tal” means “valley” in German.

Although the skull was as large as that of today’s human being, it also showed clear differences.

Compared to present-day humans, the Neanderthals had more pronounced eyebrow bulges and a fleeing forehead. Neanderthals also had a chinless face with peculiar nasal cavities, which made it easier to warm up cold air when inhaling.

The cause of their extinction remains highly contested. Demographic factors like small population size, inbreeding, and random fluctuations are considered likely factors.

Researchers from the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics in Dresden cooperated with scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig – both situated in the State of Saxony – for their study on neuronal developments.

The Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science is an independent association of research institutes.

Max Planck (1858-1947) was a German theoretical physicist and Nobel Prize in Physics laureate.

To find out more about the author, editor or agency that supplied this story – please click below.

Story By: Thomas Hochwarter, Sub-Editor: Joe Golder, Agency: Newsflash

The Ananova page is created by and dedicated to professional, independent freelance journalists. It is a place for us to showcase our work. When our news is sold to our media partners, we will include the link here.