The scientist who reported the strong possibility that prehistoric Megalodon shark babies were cannibals that would eat their siblings in the womb to make sure they were bigger and stronger when born says he knew he wanted to study the giant sharks ever since finding one of their teeth on a beach in Japan aged 13.

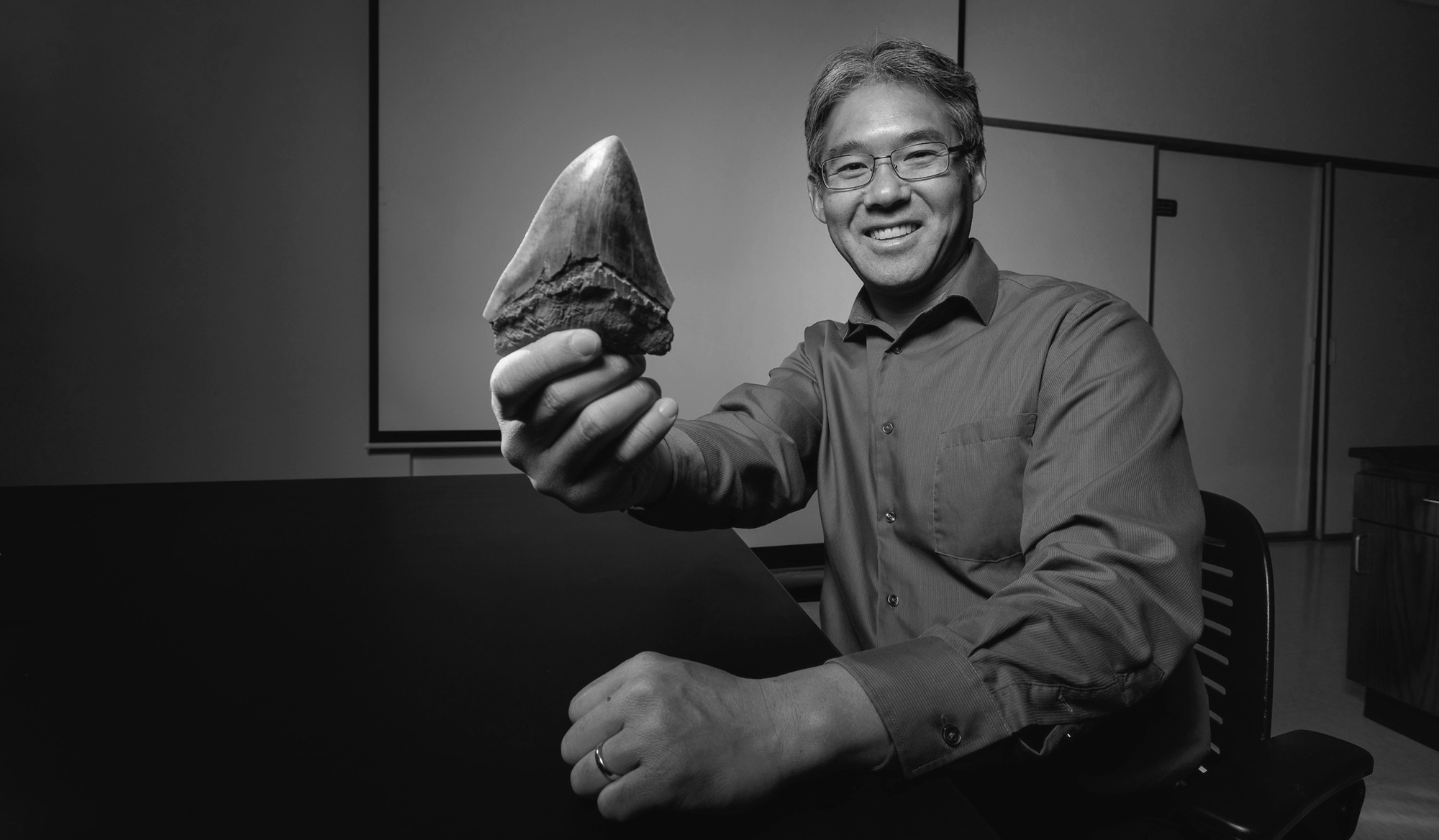

Megalodon was the largest predatory shark that ever lived in the world’s oceans and Real Press spoke to the Megalodon expert, palaeontology Professor Kenshu Shimada at DePaul University in Chicago, in Illinois, in the USA, to find out more about his work.

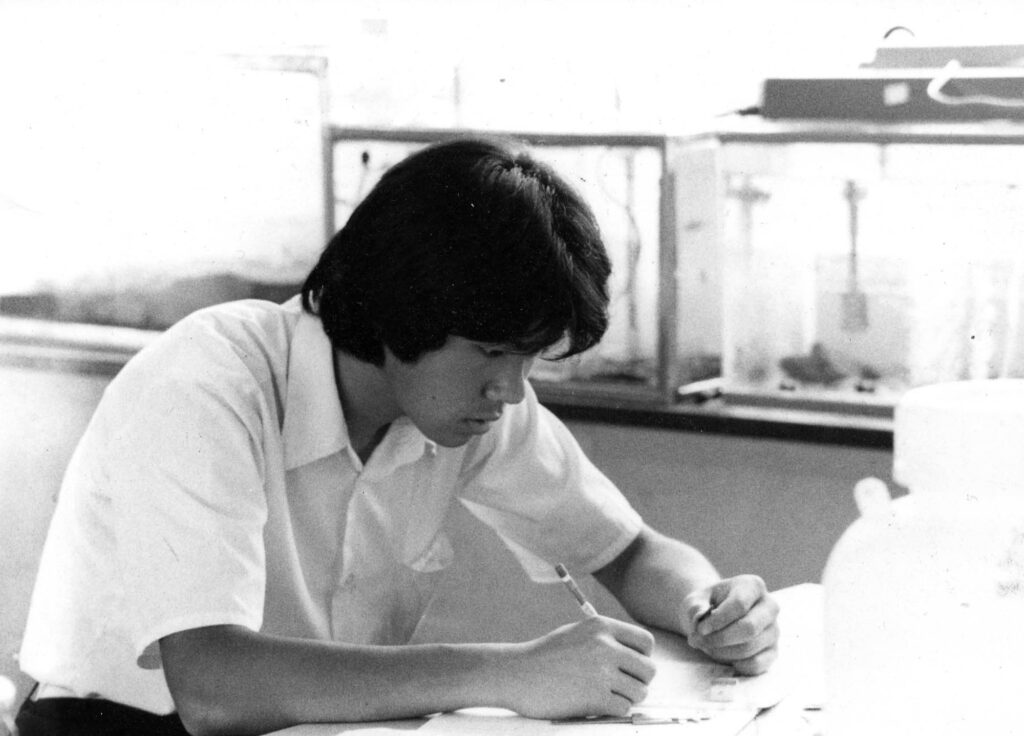

He said: “I started to develop a keen interest in fossils around 12, and at age 13, I visited a fossil site featured in a geology guidebook – this was in Japan, not far from Tokyo – where I fortuitously discovered a two-inch-tall Megalodon tooth and became particularly interested in studying fossil sharks.”

He added: “I moved to the United States after graduating high school to receive my formal university training in paleontology, the scientific study of prehistoric life. It may sound a bit geeky but understand the ecology and evolution of fossil sharks is my hobby, and I am very fortunate to have a career that allows me to do that and to share my interests with my students and others.”

His recent study, ‘Ontogenetic growth pattern of the extinct megatooth shark Otodus megalodon—implications for its reproductive biology, development, and life expectancy’, which he co-authored with Matthew Bonnan from Stockton University in Galloway, in New Jersey, and Martin Becker and Michael Griffiths, both from the Department of Environmental Science at William Paterson University, also New Jersey, was published in the academic journal Historical Biology on 11th January.

It generated international headlines this week with catchy claims that Megalodon babies were cannibals in the womb, but Professor Shimada has clarified that this is not yet a certainty, only that the study is indicative that this was the case.

He said: “The new study demonstrating that the large size at birth for Megalodon, that belongs to the shark group called Lamniformes, has really strengthened the idea that, like in the present-day lamniform sharks, intrauterine cannibalism occurred in the fossil species at least in the form of oophagy or egg-eating.

“Nourishing embryos through oophagy that grew to a large size must have been energetically costly for Megalodon mothers, but the cost must have been offset by the benefits of newborns having an advantage of being ‘already-large’ predators with a reduced risk of being eaten by other predators. At least the present-day sandtiger shark is known to also occasionally even feed on other hatched siblings for nourishment, but whether or not Megalodon embryos actually cannibalised other embryos in their mother’s womb remains to be uncertain.”

The study argues that the prehistoric Otodus Megalodon shark, that lived in the world’s oceans between 15 million and 3.6 million years ago, gave birth to giant, 6-foot shark babies that were most likely cannibals in the womb.

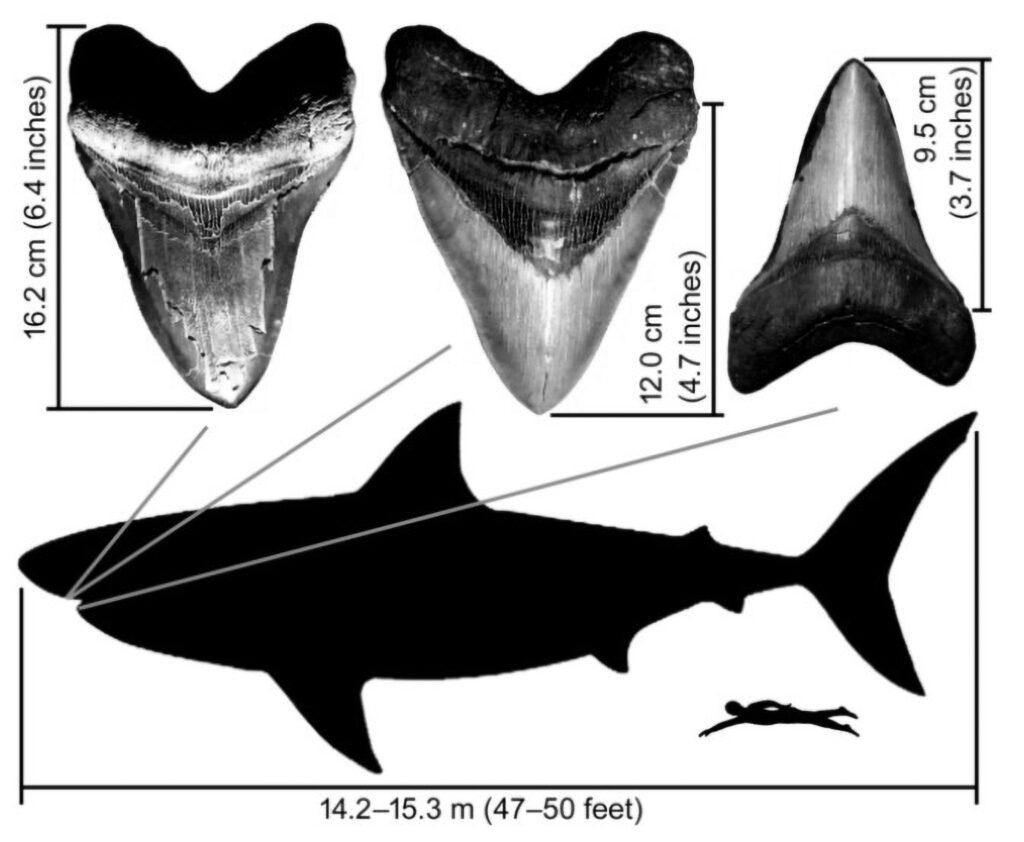

The tooth of an extinct shark Otodus megalodon

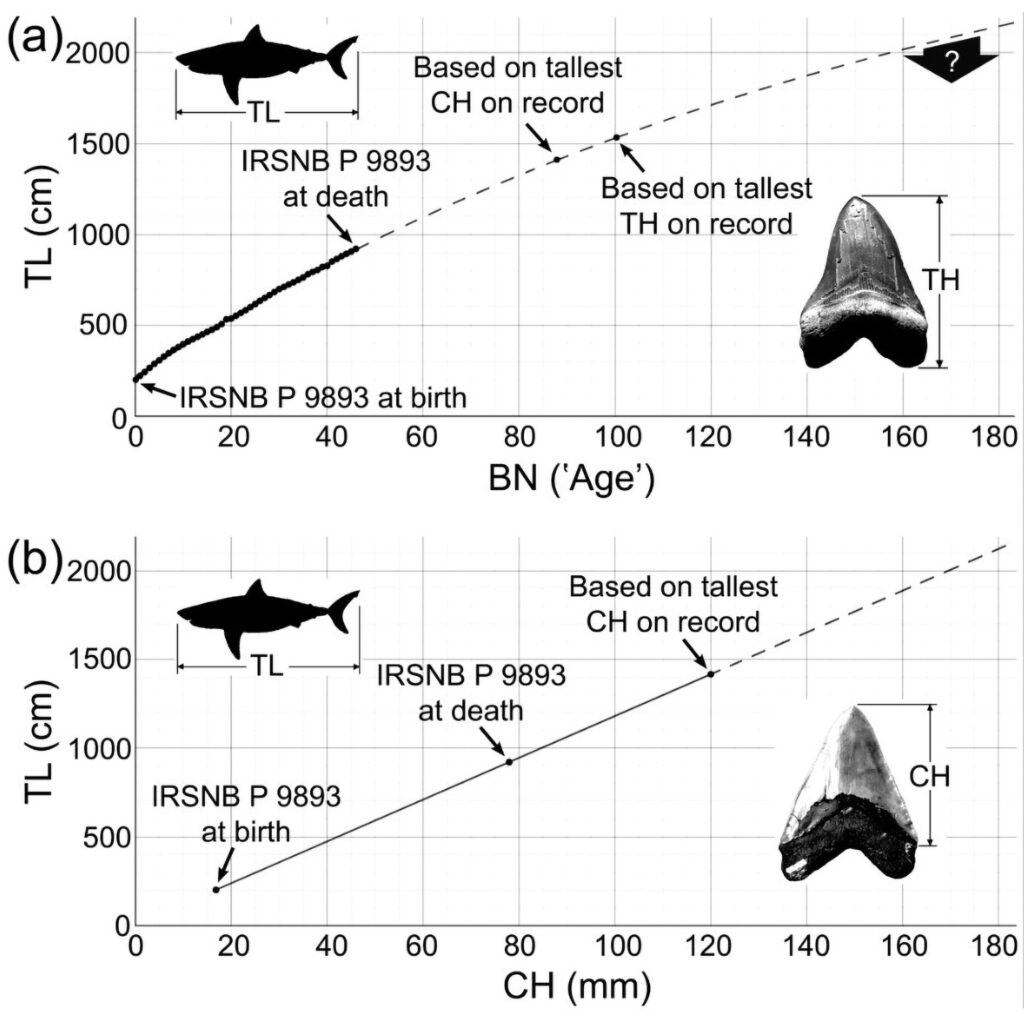

Growth models of Otodus megalodon

Professor Shimada, 52, said: “The new study examined a specimen of Otodus megalodon that consists of about 150 vertebrae recovered from a Miocene (roughly 15 million years old) rock in Belgium in the 1860s and is currently housed in the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences in Brussels.”

He added: “The cartilaginous skeleton in some sharks, including the Megalodon specimen in the new study, is well calcified, referred to as ‘calcified cartilage.”

He said that while it was unknown what caused the 46-year-old shark to have died, when other members of the species are believed to have been able to live to about 100 years old, the study did reveal that “the large size at birth for Megalodon also indicates that it must have given live birth, rather than the mother Megalodon laying eggs outside of her body.”

Looking to the future now that this groundbreaking study has been published, Professor Shimada said: “While the new study has given us a pretty good idea about the growth pattern between birth and ‘middle-age’ for Megalodon, the exact growth pattern past 46 years old, including its inferred life expectancy of at least 88-100 years, remains rather theoretical and needs further investigation.”

The Ananova page is created by and dedicated to professional, independent freelance journalists. It is a place for us to showcase our work. When our news is sold to our media partners, we will include the link here.