Experts have studied a rare African parchment in their search for clues about the evolution of writing, which they say has evolved “to become simpler and more efficient”.

The Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History said in a statement released on Thursday 13th January and obtained by Newsflash: “Writing evolves to become simpler and more efficient.”

This is according to the new study, which is based on an “analysis of an isolated West African writing system”.

The Max Planck Institute explained that the world’s very first invention of writing occurred over 5,000 years ago, in the Middle East, before it was reinvented in China and Central America.

The Institute added: “Today, almost all human activities—from education to political systems and computer code—rely on this technology.”

The team of researchers at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany, showed that writing very quickly “becomes ‘compressed’ for efficient reading and writing.”

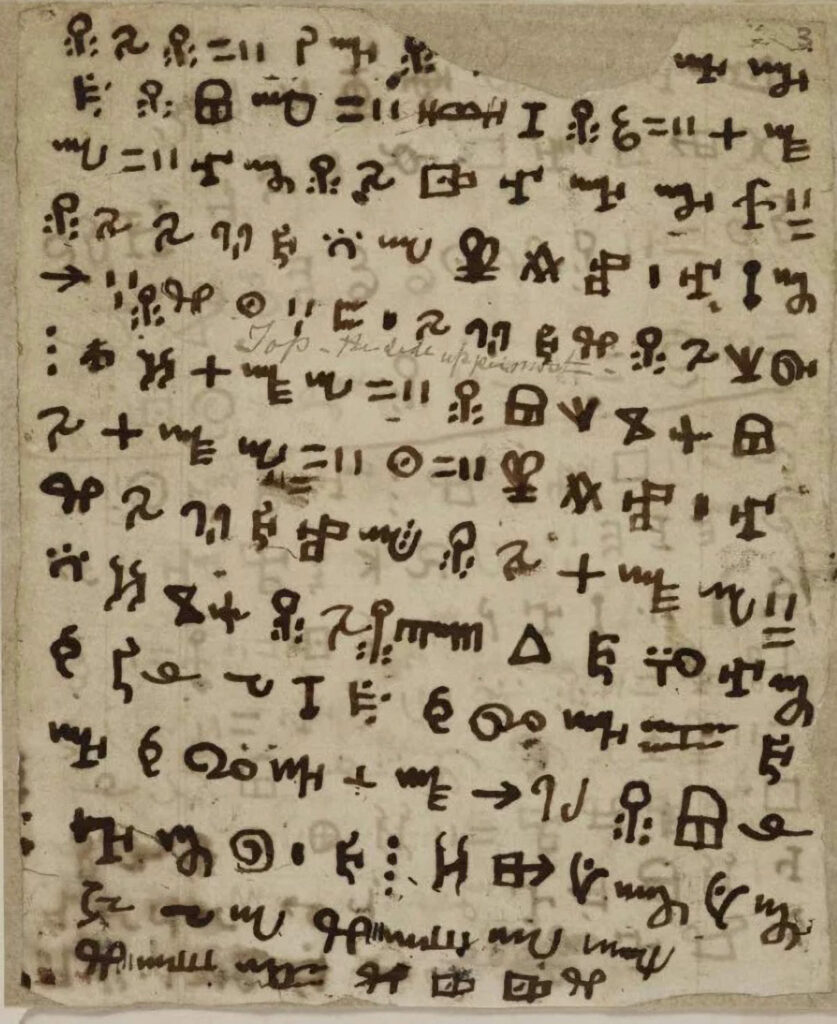

The statement said: “To arrive at this insight they turned to a rare African writing system that has fascinated outsiders since the early 19th century.”

(The British Library, CC0/Newsflash)

Lead author Dr Piers Kelly, now at the University of New England, Australia, said: “The Vai script of Liberia was created from scratch in about 1834 by eight completely illiterate men who wrote in ink made from crushed berries.”

The Vai language had never been written down before and according to Vai teacher Bai Leesor Sherman, the script “was always taught informally from a literate teacher to a single apprentice student. It remains so successful that today it is even used to communicate [COVID-19] pandemic health messages.”

Dr Kelly added: “Because of its isolation, and the way it has continued to develop up until the present day, we thought it might tell us something important about how writing evolves over short spaces of time.”

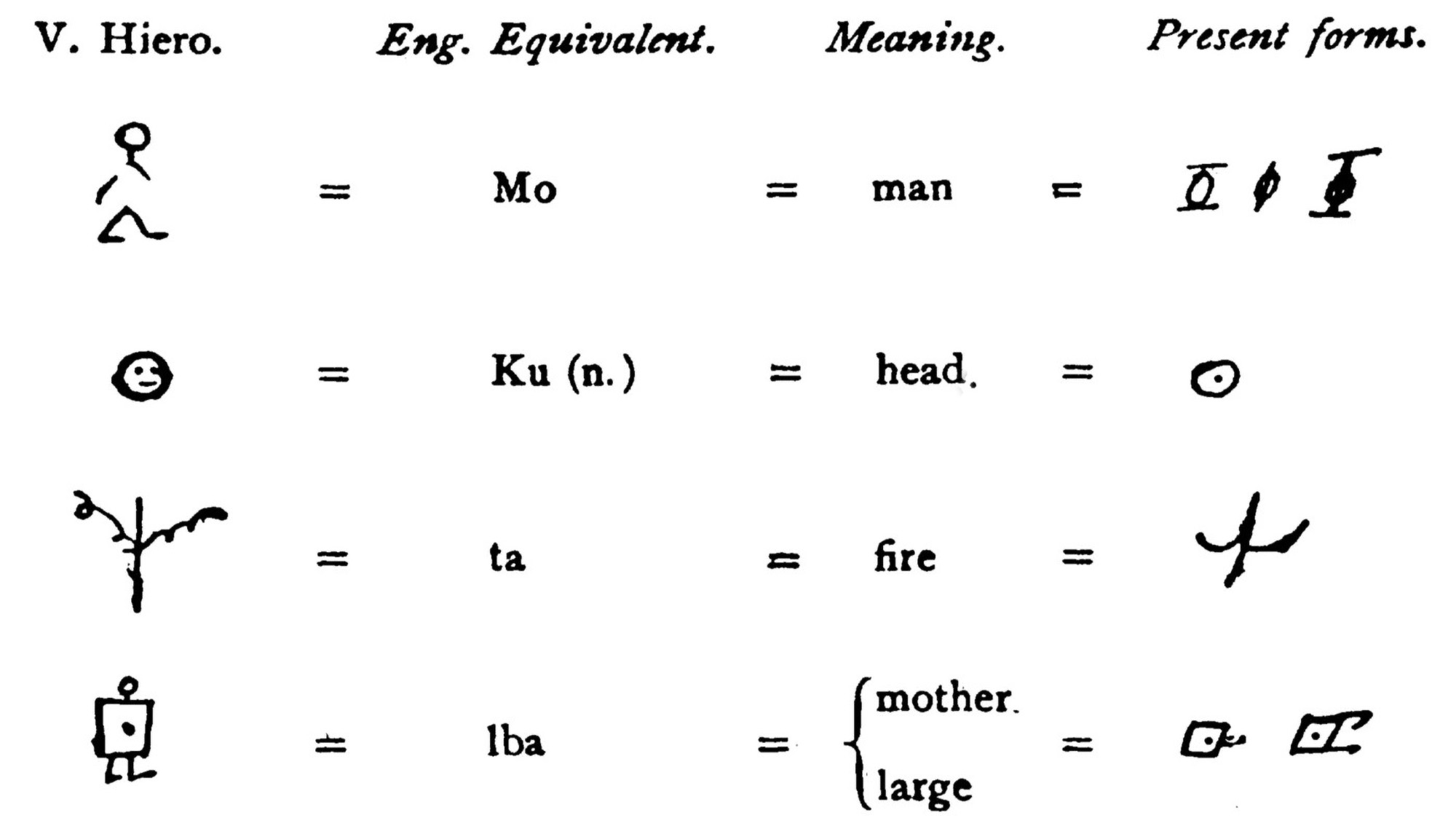

He added: “There’s a famous hypothesis that letters evolve from pictures to abstract signs. But there are also plenty of abstract letter-shapes in early writing. We predicted, instead, that signs will start off as relatively complex and then become simpler across new generations of writers and readers.”

The team of experts analysed manuscripts in the Vai language from archives in Liberia, in the United States, and in Europe.

They said that by “analysing year-by-year changes in its 200 syllabic letters, they traced the entire evolutionary history of the script from 1834 onwards. Applying computational tools for measuring visual complexity, they found that the letters really did become visually simpler with each passing year.”

Dr Kelly said: “The original inventors were inspired by dreams to design individual signs for each syllable of their language. One represents a pregnant woman, another is a chained slave, others are taken from traditional emblems.

“When these signs were applied to writing spoken syllables, then taught to new people, they became simpler, more systematic and more similar to one another.”

Dr Kelly added: “Visual complexity is helpful if you’re creating a new writing system. You generate more clues and greater contrasts between signs, which helps illiterate learners. This complexity later gets in the way of efficient reading and reproduction, so it fades away.”

Inventors have reverse engineered writing down spoken languages elsewhere in West Africa, in Mali and Cameroon, while “new writing systems are still being invented in Nigeria and Senegal”.

Nigerian philosopher Henry Ibekwe said, in response to the study: “African indigenous scripts remain a vast, untapped repository of semiotic and symbolic information. Many questions remain to be asked.”

The study has been published in the academic journal Current Anthropology.

To find out more about the author, editor or agency that supplied this story – please click below.

Story By: Joseph Golder, Sub-Editor: William McGee, Agency: Newsflash

The Ananova page is created by and dedicated to professional, independent freelance journalists. It is a place for us to showcase our work. When our news is sold to our media partners, we will include the link here.