Archaeologists have discovered a beautifully preserved fossil of an extinct turtle that thrived when the south of Europe was still a tropical paradise 150 million years ago.

The so far best-conserved specimen of the extinct animal – Solnhofia parsonsi – was reportedly found in limestone deposits in a quarry pond in the Painten district, near the city of Regensburg, Bavaria State.

Researchers at the University of Tuebingen, Germany, said the turtle – named after the Solnhofen Limestone fossil bed that preserves a rare assemblage of fossilised organisms – lived during the Late Jurassic.

The famous site has reportedly produced some of the most unique fossils in the world including the early feathered avian dinosaur Archaeopteryx, known as the oldest ever known bird.

The archaeologists said the ancient turtle’s fore and hind limbs were quite short in comparison to modern sea turtles, suggesting that it inhabited coastal areas.

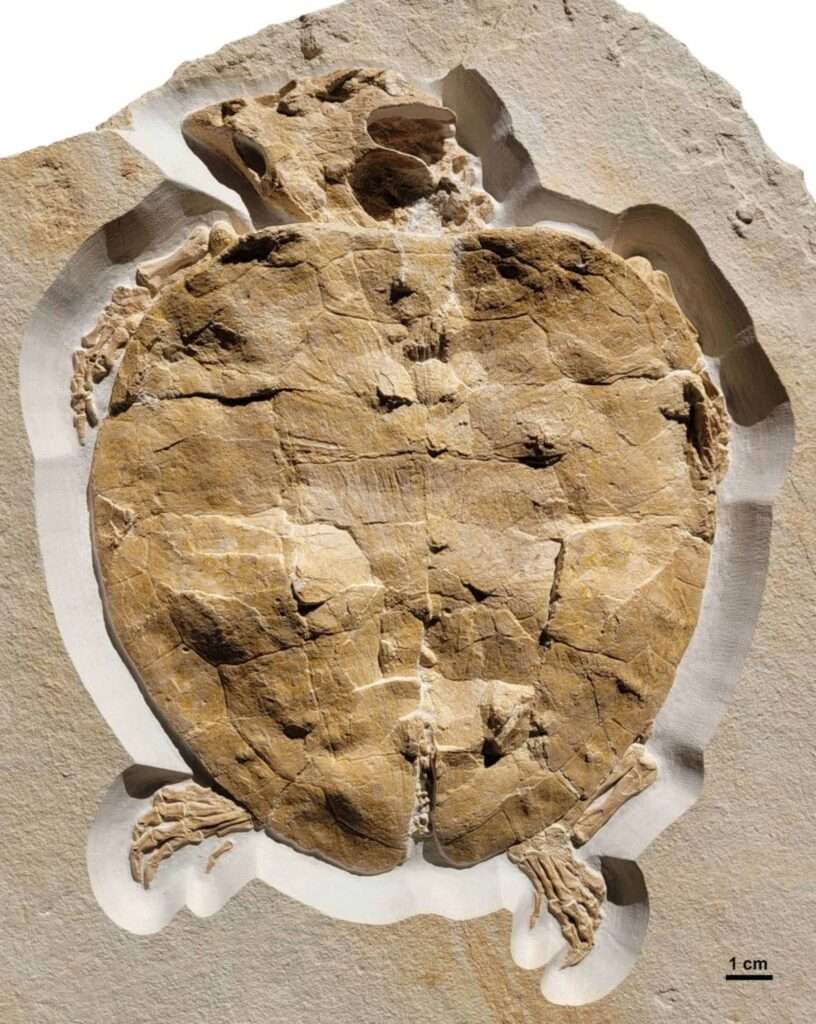

An image released by the researchers showed the 150 million-year-old turtle’s nine-centimetre-long (3.5 inches) triangular head and more than twice as big carapace, as well as its long and pointed beak.

Researcher Felix Augustini said in a statement obtained by Newsflash from the University of Tuebingen: “No Solnhofia individual with such completely preserved extremities has ever been described before.

Archaeologist and co-author of the study Marton Rabi said: “Solnhofia may have used its large head to crush hard food items such as shelled invertebrates, as we see in some modern turtles, but it does not mean these were exclusively forming its diet.”

Both species reportedly lived about 150 million years ago when a tropical sea stretched across the southern part of the country.

It reportedly contained many islands and reefs that separated basins from the open sea, as floating particles sinking to the basin floors formed layers of limestone.

The university said: “If an animal died, its remains also sank to the bottom.

“Due to the low exchange of the lagoon water with the open sea, the oxygen content there was so low and the salt content so high that dead plants and animals did not decompose.

“Plant and animal remains were preserved and fossilised in the limestone – often in unique detail.”

Co-author of the study Andreas Matzke from the University of Tuebingen said: “The very good preservation of the fossils in the layers of limestone can be explained by the environmental conditions at the time.”

The study was published in the peer-reviewed open access journal ‘PLOS ONE’ on Wednesday, 26th July.

To find out more about the author, editor or agency that supplied this story – please click below.

Story By: Georgina Jadikovska, Sub-Editor: Marija Stojkoska, Agency: Newsflash

The Ananova page is created by and dedicated to professional, independent freelance journalists. It is a place for us to showcase our work. When our news is sold to our media partners, we will include the link here.