Prehistoric dinosaur birds preferred to snack on insects instead of fish, a new study has revealed.

It had been believed that the 120 million-year-old Longipterygidae family’s long beaks with sharp teeth at the tip put them in a similar class to modern kingfishers.

Now new research has shown that the strange avians actually ate insects rather than fish.

Dr Michael Pittman and his team identified the diet of a group of prehistoric birds in The Chinese University of Hong Kong’s (CUHK) School of Life Sciences, in the city of Hong Kong, located in Southern China.

The study was published in the international journal of biology BMC Biology, on the 12th May.

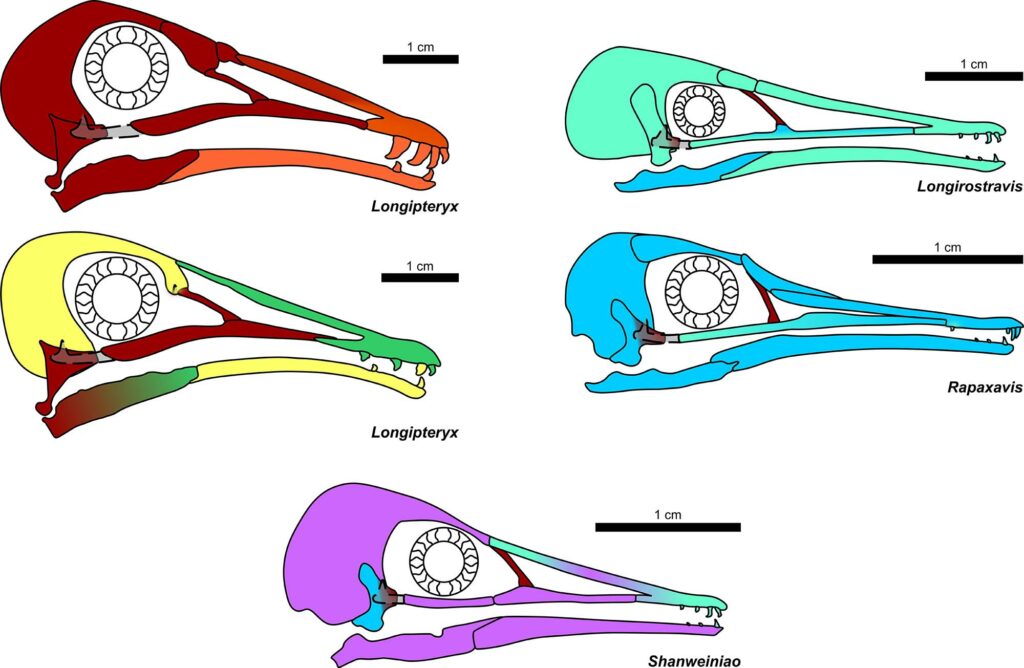

(Julius T. Csotonyi/AsiaWire)

Pittman and his team investigated previous assumptions made about these birds’ diet based on quantitative fossil evidence.

The team investigated more than 150 living bird species, combining four separate lines of evidence – body mass, claw shape, skull bite efficiency and skull bite strength – to reconstruct the diet of the ancient birds.

Rather than eating fish, the team found that they were most likely to feed on invertebrates like insects, or to eat a variety of foods.

The study focused on the feeding habits of the Longipteryx, a member of the wider Longipterygidae family.

Case Vincent, first author of the research and Dr Pittman’s PhD student, said: “Longipteryx birds have a smaller body mass and in particular weaker jaws than most living fish-eating birds like kingfishers.

“The evidence pointing to Longipteryx not being a specialist fish-eater surprised me the most, as it was previously assumed that was why they evolved such long jaws.”

This means birds in the longipterygid family were evolving their long snouts while keeping the same diet as their ancestors, which suggests their unique skulls evolved for a reason other than a change in diet.

(Case Vincent Miller/AsiaWire)

The study hypothesizes that the strange jaws of longipterygids may have helped in removing parasites, cooling down their body, or enhancing their senses in some way.

Pittman said: “There is still a lot of work to do, which includes adding additional methodologies to narrow dietary habits further, to form a more complete record of bird ecology”.

Pittman added: “Birds eat just about everything today, but the origin of such a range of diets is a mystery.

“Understanding the diet of extinct birds is key to understanding their ecology, and in turn prehistoric ecology as a whole.”

The Ananova page is created by and dedicated to professional, independent freelance journalists. It is a place for us to showcase our work. When our news is sold to our media partners, we will include the link here.