Recently discovered beetle fossils preserved in amber for hundreds of millions of years have revealed that the bugs ate dinosaur feathers, according to a new study.

The study shows how the beetles were trapped inside the amber fragments 105 million years ago along with pieces of feathers.

The experts said that these could not have belonged to birds, which appeared 30 million years later, and that they belonged to feathered dinosaurs.

The study, therefore, shows that the bugs and the dinosaurs, from the Early Cretaceous period, had a mutually beneficial and symbiotic relationship that allowed them to help each other evolve over time.

The academic article was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on Monday, 17th April, and Newsflash obtained a statement from the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom saying: “New fossils in amber have revealed that beetles fed on the feathers of dinosaurs about 105 million years ago, showing a symbiotic relationship of one-sided or mutual benefit, according to an article published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America today.”

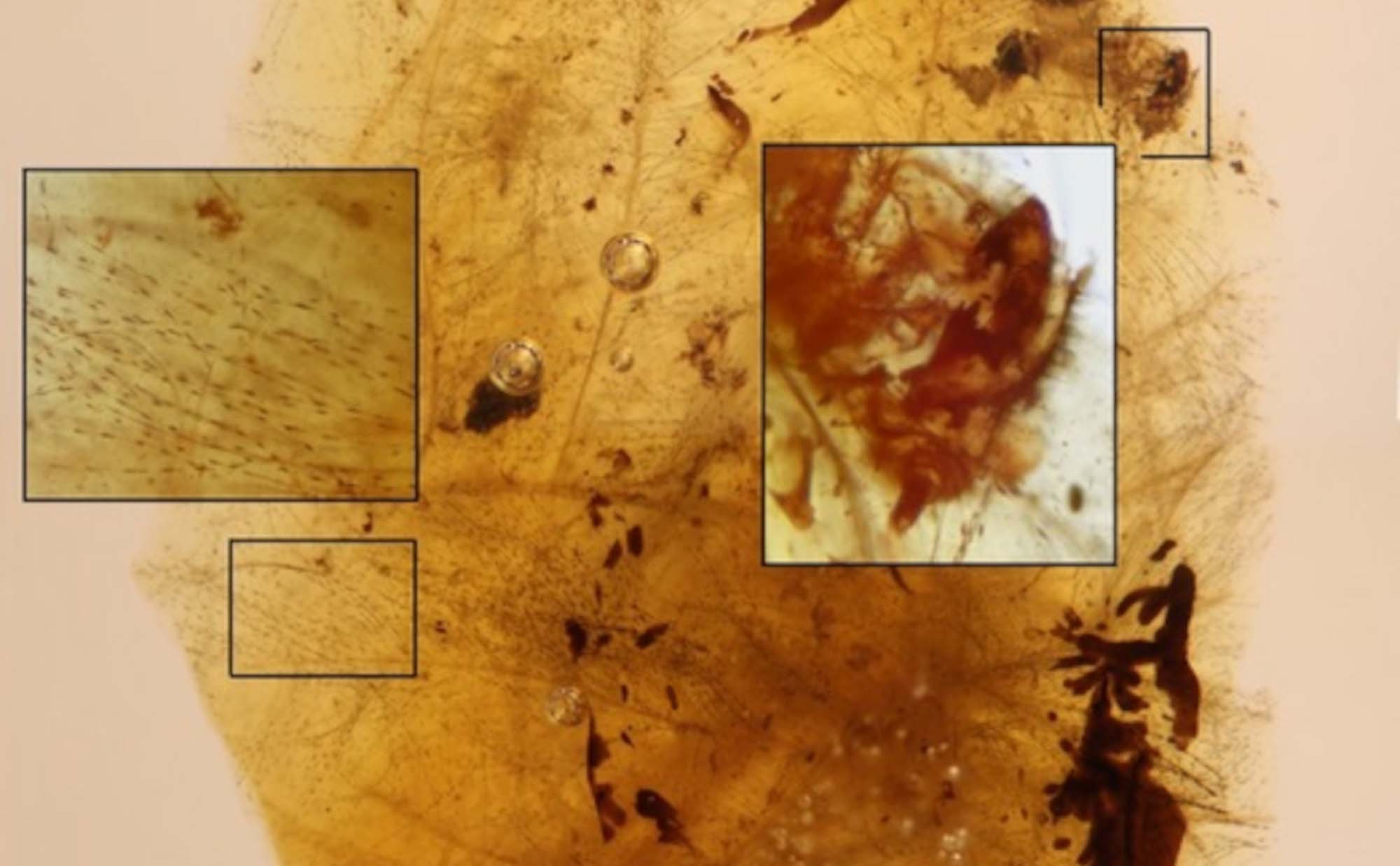

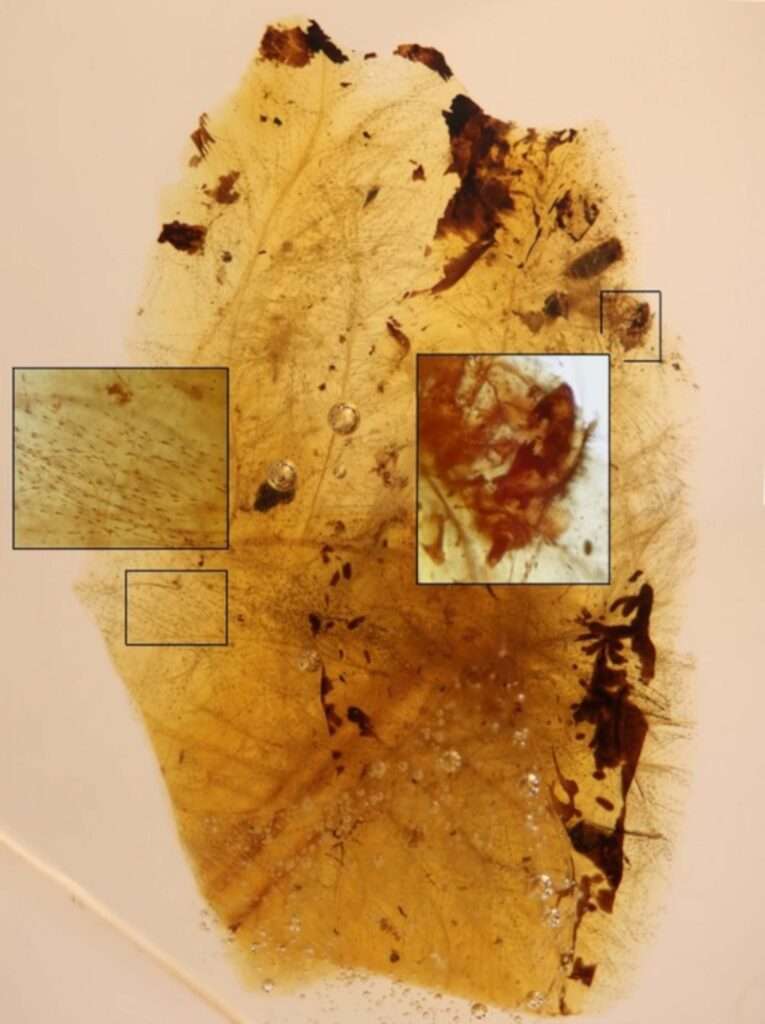

The statement said: “The main amber fragments studied, from the Spanish locality of San Just (Teruel), contain larval moults of small beetle larvae tightly surrounded by portions of downy feathers.

“The feathers belonged to an unknown theropod dinosaur, either avian (a term referring to ‘birds’ in wide sense) or non-avian, as both types of theropods lived during the Early Cretaceous and shared often indistinguishable feather types.

“However, the studied feathers did not belong to modern birds since the group appeared about 30 million years later in the fossil record, during the Late Cretaceous.”

The experts believe that the interactions between the two species led to them evolving together.

The statement said: “When looking at modern ecosystems, we see how ticks infest cattle, frogs capture insects with acrobatic tongues, or some barnacles grow on the skin of whales.

“These are just a few of the diverse and complex ecological relationships between vertebrates and arthropods, which have coexisted for more than 500 million years.

“The way that these two groups have interacted throughout deep time is thought to have critically shaped their evolutionary history, leading to coevolution. Nevertheless, evidence of arthropod-vertebrate relationships is extremely rare in the fossil record.”

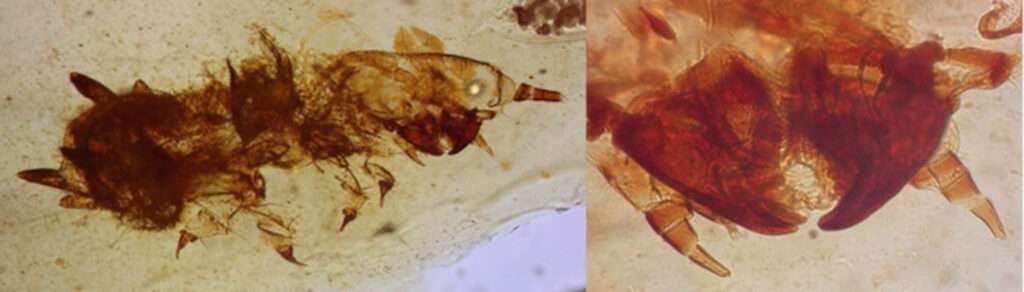

The statement also said: “The larval moults preserved in the amber were identified as related to modern skin beetles, or dermestids. Dermestid beetles are infamous pests of stored products or dried museum collections, feeding on organic materials that are hard for other organisms to decay such as natural fibres.

“However, dermestids also play a key role in the recycling of organic matter in the natural environment, commonly inhabiting nests of birds and mammals, where feathers, hair, or skin accumulate.”

Dr Enrique Penalver, from the Geological and Mining Institute of Spain of the Spanish National Research Council (CN IGME-CSIC), the lead author of the study, said: “In our samples, some of the feather portions and other remains – including minute fossil faeces, or coprolites – are in intimate contact with the moults attributed to dermestid beetles and show occasional damage and/or signs of decay.

“This is hard evidence that the fossil beetles almost certainly fed on the feathers and that these were detached from its host.”

He added: “The beetle larvae lived − feeding, defecating, moulting − in accumulated feathers on or close to a resin-producing tree, probably in a nest setting. A flow of resin serendipitously captured that association and preserved it for millions of years.”

Dr David Peris, from the Botanical Institute of Barcelona (CSIC-Barcelona City Council) and co-author of the study, said: “Three additional amber pieces each containing an isolated beetle moult of a different maturity stage but assigned to the same species were also studied, allowing a better understanding of these minute insects than what is usually possible in palaeontology.”

Dr Ricardo Perez-de la Fuente, from the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, a co-lead author of the study, said: “It is unclear whether the feathered theropod host also benefitted from the beetle larvae feeding on its detached feathers in this plausible nest setting.”

He added: “However, the theropod was most likely unharmed by the activity of the larvae since our data show these did not feed on living plumage and lacked defensive structures which among modern dermestids can irritate the skin of nest hosts, even killing them.”

To find out more about the author, editor or agency that supplied this story – please click below.

Story By: Joseph Golder, Sub-Editor: Michael Leidig, Agency: Newsflash

The Ananova page is created by and dedicated to professional, independent freelance journalists. It is a place for us to showcase our work. When our news is sold to our media partners, we will include the link here.